Your Smartphone: The Modern-Day Parasite

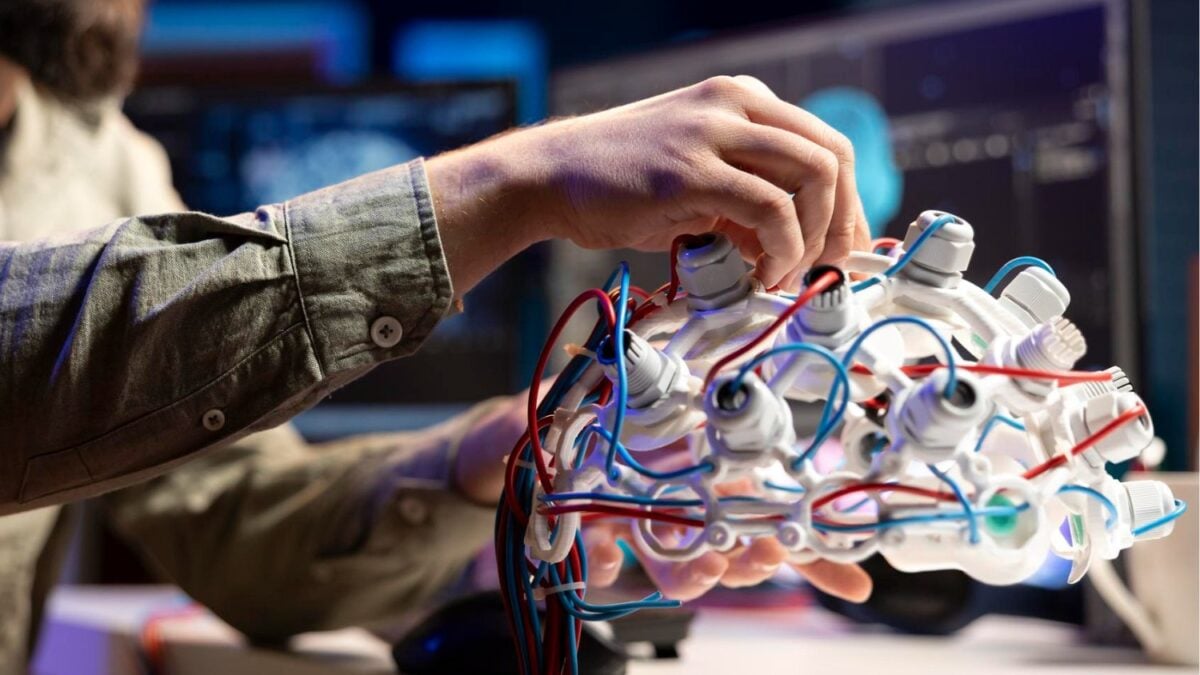

Throughout history, humans have coexisted with parasites like head lice and tapeworms. However, in today's world, the most pervasive parasite isn't a blood-sucking invertebrate but a sleek, glass-fronted device: the smartphone. With its host being anyone with a WiFi signal, smartphones have become a modern-day parasite.

While smartphones are often seen as useful tools, they parasitize our time, attention, and personal information, serving the interests of tech companies and advertisers. A recent article in the Australasian Journal of Philosophy highlights the societal risks posed by smartphones through the lens of parasitism.

Parasites are defined by evolutionary biologists as species that benefit from a close relationship with a host, which bears a cost. For example, head lice depend entirely on humans for survival, feeding on our blood and providing nothing in return but an itch.

Smartphones have revolutionized our lives, aiding in navigation and health management. Despite these benefits, many are enslaved to their devices, suffering from sleep deprivation, weakened relationships, and mood disorders.

Not all close relationships between species are parasitic. Some, like the bacteria in animal digestive tracts, are mutualistic, providing benefits such as improved immunity. Initially, smartphones were mutualistic, helping humans stay connected and informed. However, this relationship has evolved into a parasitic one, similar to natural occurrences where mutualists become parasites.

Smartphones have become indispensable, yet many apps prioritize the interests of companies over users. These apps are designed to keep us scrolling and clicking, exploiting our behavior for profit. This parasitic relationship raises questions about the future and how to counteract these high-tech parasites.

In nature, mutualistic relationships can shift to parasitism, as seen with the bluestreak cleaner wrasse and reef fish. The fish may punish the wrasse for cheating, demonstrating the importance of policing to maintain balance. Similarly, we need to police our smartphone usage to restore a beneficial relationship.

Detecting smartphone exploitation is challenging, as tech companies don't advertise their manipulative designs. Even when aware, it's difficult to resist, as we've become reliant on smartphones for daily tasks, affecting our cognition and memory.

Governments and companies have increased our dependence on smartphones by moving services online. This dependency makes it hard to fight back. Individual choices are insufficient against tech companies' information advantage. Collective action, like the Australian government's social media age restrictions, is necessary to limit smartphone exploitation.

To reclaim a mutualistic relationship with smartphones, we need restrictions on addictive app features and data collection. Only through collective action can we hope to win this battle against our modern-day parasites.